Diana Brodie's first, overdue book begins by exploring the differences between the mundane and the conceptual/spiritual. Music and Art mediate, and Doubt is always a risk.

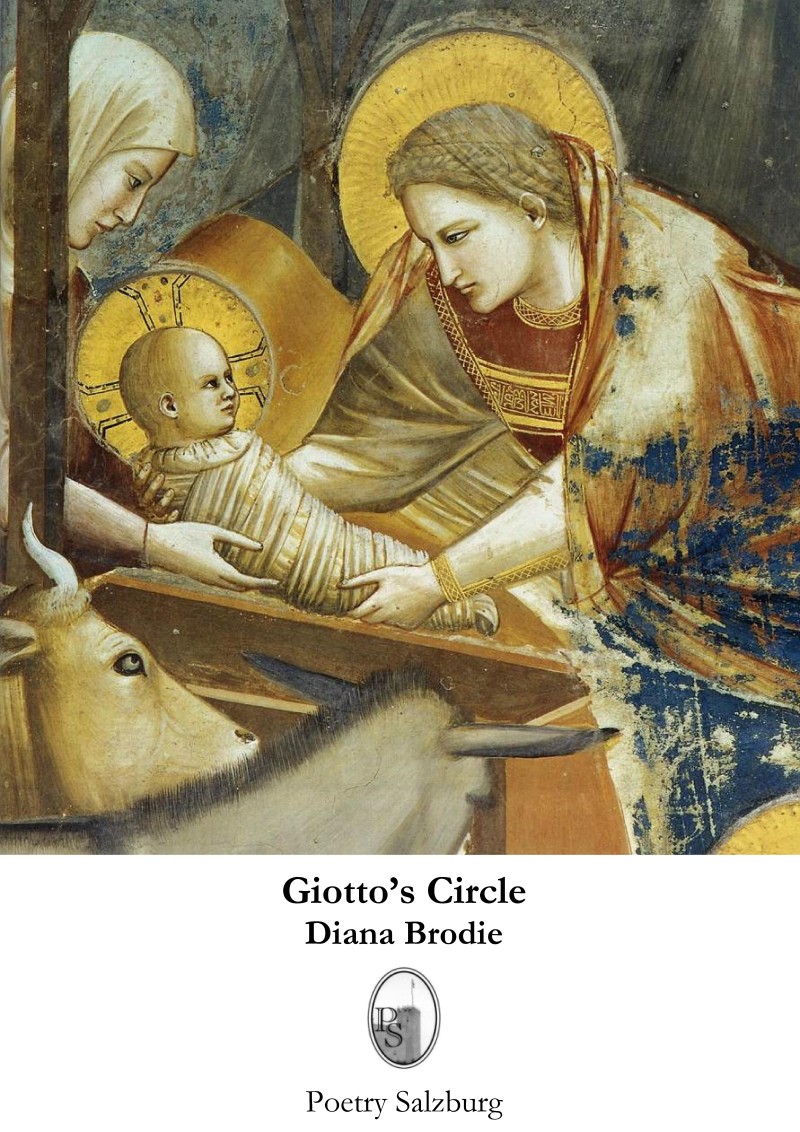

In the title poem a messenger is worried that presenting Giotto's proof of his skill (a hand-drawn circle) to the Pope won't go down well. It's true that no physical circle can ever match the perfection of x2+y2=r2, but we inhabit a physical world, communicating using images. Even if human imperfection isn't all we have, we may as well do the best we can in this world.

Diana Brodie's first, overdue book begins by exploring the differences between the mundane and the conceptual/spiritual. Music and Art mediate, and Doubt is always a risk.

In the title poem a messenger is worried that presenting Giotto's proof of his skill (a hand-drawn circle) to the Pope won't go down well. It's true that no physical circle can ever match the perfection of x2+y2=r2, but we inhabit a physical world, communicating using images. Even if human imperfection isn't all we have, we may as well do the best we can in this world.

After the initial section, autobiography begins to take over. Even the poems about other people and places concern incidents that the poet has witnessed. One can almost trace the effect of (or rebellion against) the influences down through the poet to the later generations in the final section.

Syntax is conversational throughout (in several poems I'd have doubled the line-length and halved the number of lines), though the narrative pacing varies - poems like "Earthquake City" cover many years; "The Trap" is a poem that covers a few minutes and depends on its punchline. The poems have cumulative power, improved by each other's company. Though there are few knock-out pieces, there are few if any duds. The 65 poems (villanelles, sonnets, rhyming couplets, and terza rima as well as free verse; from "Agenda", "The Rialto", "Smiths Knoll", etc) are loosely organised into 7 sections whose titles are adapted from lines in the poems.

- No ordinary thing - transcendence; the arts

- No river where the river was - water; regeneration

- Too high for jumping - father

- Was it Maman? - mother; New Zealand

- Was there a message to deliver? - brother; messages from the past

- We walk the tightrope of the air - sister; childhood

- … and balance there - the here and now

The final poem of each section often seques into the next.

It's tempting to assume that all the first person narrators (except in the Dame Edith poem) are the poet. By making that assumption, more threads and narratives emerge. For example, in "Windfall", the father "can't forget/ fine windfall fruit/ behind a wall/ too high for jumping". 3 poems later, in "Across the Bar", father sits the narrator "on the bar of his big black Raleigh bike". She hasn't jumped yet but she's halfway over, on the move. In the next poem we read "All that summer when I was ten,/ I practised jumping", as if the narrator doesn't want to make the mistake her father did. Her father tells her that there might be nobody, not even the fisherman (Christ?) to save her if she gets into trouble. The later "Wordfall" (contrasting with "Windfall") might be my favourite poem in the book.

In "At Golden Bay" we wonder why the narrator's stuck inside the holiday house for 2 weeks. At the end, on the drive home, we read that the family "grew used to Mum's sharp intakes of breath/ before each hairpin bend". This is our first encounter with the mother who seems to have a restraining, dominating effect on her children, a restraint compounded by the New Zealand context of the time, where a woman wearing a hat but not gloves might be considered a hussy. The father adapts to the limitations. In "Take it from here" he has to listen to his favourite comedy program "just audible with the volume turned down low". In "Dove Cottage" the father gives the narrator a tiny porcelain house that grew warm in her hands. In contrast, the home seems less cosy.

|

Late that night I wrote a poem. Mum found it, tore it up, put the pieces in the bin. |

The narrator learns from this too. In "Bev's Typewriter"

|

I

dismembered her typewriter on the kitchen table, struggled to find a place for those parts that I was left with, learned to type by touch |

Once the "Was there a message to deliver?" section is read it's also tempting to see all brothers (indeed, all boys) as her brother. "Gregor: Metamorphosis" might well be about him. In "Lizard" the narrator catches a lizard ("like ancient Demeter's lizard boy" - Demeter changed a man into a lizard because he laughed at the way she was drinking) and zips it in a purse, but the purse is empty by the time the narrator's back at their house - the emptiness is "His gift", the final line says. In "The Axe" the narrator flies in a Cessna over the place where her brother died. The pilot's blasé about flying, and is prepared for the worst

|

he told us about the axe kept under the front passenger seat in case any of us needed to smash our way out |

Another axe appears in "Missing", when a year's losses are listed.

By no means all the pieces are this personal though. "Glass Heads" is typical of the poems that make further metaphors from material already rich in potential. A sculptor makes hollow glass heads with "no eyes to see or mouths to speak". The act of breathing life into them can be compared to artistic creation. They're exhibited at Prague Museum, each with a clue to their identity. Terezin's nearby, adding layers to the metaphorization. In "Rainy Sunday in Bordeaux" there's a Door Museum with "doors offering nothing to us/ but themselves".

Several of the character studies feature off-centre people whose behaviour highlights central concerns

- In "Water" we meet a little boy (autistic?) who plays obsessively with water from a pool, lifting cups and tipping them slowly or quickly. Ten years later the pool's been drained.

The boy lies on the sofa, eyes closed, silent.

His elder brother leans across to lift him,

then brings to his, tips up, the covered cup.

The boy drinks water. - In "Board and Lodging", Mr McDowell's behaviour warrants explanation, but the one that his wife provides doesn't explain much.

- In "Angel of the East" an angel returns to sit on Dresden shoe factory, then flies for the sheer joy of it.

- In "Not as arranged" a doctor "in his eco-friendly, ergonomic chair" looks out at his new Zen garden to see deranged Rhoda, "Naked. Singing. Dancing. Waving. Drinking".

Music (Fauré, Bach, etc) receives several mentions, as does art. Flaubert's mentioned, and the brother's lost novel, but no poets or poems are alluded to. The final poem contrasts with the book's first, "Giotto's Circle", by being nearly a poetry-about-poetry piece, a credo. Its final line is "The pen ekes out words in end-stopped lines. The circle falls apart".

That "falling apart" might be no bad thing - circles signify closure/finality as well as completion. On the cover the infant Jesus seems more bound than swaddled. Like Mr McDowell's sawing, the doors in the Bordeaux museum, or the hollow glass heads, the world might be what we experience and nothing more. The title poem mentioned at the top of this article doesn't end with the messenger's misgivings or faith in the transcendent. We're returned back to the contemporary, real (albeit artistic) world. The poet/narrator continues through the Scrovegni Chapel to enter "the frescoed circle", to "breathe the azure/ of the painted sky,/ breathe the stars."

No comments:

Post a Comment