When people fall in love they sometimes start writing poetry as if they're the first people to feel that way. However genuine the expression, however simple and strong the words are, the texts will have questionable value to readers unless the content or the method offers something different. Death is less frequent than love, but more reliable; no-one's exempt. Doctors have given me bad news about others. I've slept in shifts in wards, taking turns around a bed. A relative (now a nurse) had childhood leukemia. I know cancer survivors, people whose children died without warning in the night, full-time carers.

When people fall in love they sometimes start writing poetry as if they're the first people to feel that way. However genuine the expression, however simple and strong the words are, the texts will have questionable value to readers unless the content or the method offers something different. Death is less frequent than love, but more reliable; no-one's exempt. Doctors have given me bad news about others. I've slept in shifts in wards, taking turns around a bed. A relative (now a nurse) had childhood leukemia. I know cancer survivors, people whose children died without warning in the night, full-time carers.

People affected by death talk about it. Some write about it, perhaps making it their first public work - a eulogy perhaps. Eulogies needn't be original - so much is performative - but even there, some characteristic anecdotes help. At wakes, some of the best anecdotes are exchanged, honed by retelling. In such situations there are even people (not just those touched by Lady Di's death) who write poetry.

Denise Riley's technique was less strident when writing about her dead son - a common tendency, I suspect. Brenda Shaughnessy's "My Andromeda", about her son brain-damaged at birth, has a more transparent style than her earlier books. Part of the technique of writing about strong subjects might be to let the content show through. In this respect poetry has disadvantages as a vehicle. It can be viewed nowadays as pretentious, contrived. The shape of the text raises expectations that encourage inauthentic readings. The clutter of meter, rhyme and line-breaks compromise word choices and risks distracting readers.

This publication isn't the poet's first, and she's been in Magma, Stand, etc. The poet's daughter died at 16 months, ill from birth with a heart condition. Dare a reviewer adversely comment on these poems? Is it possible to offer an opinion on the poetry without taking the content into account? What happens if the opacity is restored to the language? Would the effect of the language matter much anyway? I'd hope so - after all, this is self-defined as poetry. The book's reviews have mentioned strengths that good prose about a moving subject should have. There's no reason why poetry shouldn't have those feature too, but what about poetic features? What, for example, about the linebreaks? Poetry is "the best words in the best order", wrote Coleridge. In the blurb, Bernard O'Donoghue describes the poems as "word-perfect" which they may be, but what about the words' position on the page? Perhaps, like rabbits and headlamps, readers are blinded and rendered passive by the content's intensity.

The 6 line "Fetal Heart" looks pitifully small on the page. It's an affecting ploy that can only be used once in a book. Here, appropriately, it's at the beginning. "Room in a Hospital" describes a sadly common event in a common way. 2 paragraphs of prose would have sufficed. Here we have 8 line-breaks and 5 stanza breaks, the last giving the single-line final stanza an elbow-in-the-ribs emphasis. Get it? Yes, and

I've heard it before."Skin-to-skin" is stretched to 8 lines. It sounds like the start (or a paragraph) of a short story. "Toast" (in couplets except for the

punchline

) ends with the parents wondering what faults in their bodies caused the fault in the child. That's been done too. "Echo" (more gratuitous couplets) begins "Not the one that starts in your mouth, bounces back,/ rolls down your throat, vowels collecting like balls in a net". What associations is "collecting like balls in a net" supposed to arouse? I can think of a few situation where balls are collected like this, but they're not helpful here. Nor do I recognise that echo, not as noise, tears, or regrets. A shame, because the poem's the best so far. Why isn't the line-break in stanza 4 after "marking" instead of after "hare,"? Why is there a line-break at all? Is it because so few words if formatted as prose couldn't be sold at £9.95? These are the risks that poets take.

"Palliative" cries out to be in prose. 3 paragraphs would fit the contents well, with breaks at "heart" and "gut". Each line-break's a gimmick that fails, having no function. I like "A Dream of Heart Babies" - see later. "I Sweat When I" has lines like

than mine. Weaning her

which isn't a unit of breath, thought, or anything else I can think of. Once the poem starts in short-lined couplets, all content succumbs to the chop, chop, chop of the gratuitous form. The more adventurous layout of "Swings" relates to the content, which is welcomed, but the content's weak, pedestrianly employing the old "invalid child on swing/roundabout" trope. "Ward at Night" says nothing new.

The first section of the book ends with a death. The middle section of the book, "Mining", looks back. I much prefer this section to the first. The default template is flashback (in couplets) + isolated punchline.

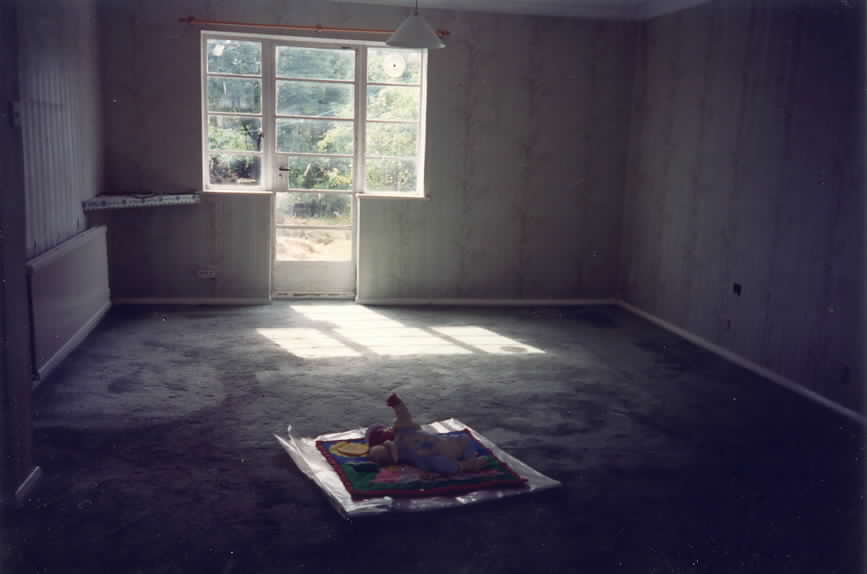

- "The Highchair" ends - "Homemade stews/ hurled frozen in a bin bag,// until it was lumpy with waste." - emptying the house is a common topic in such books. I've sorted lofts (the "For sale: baby shoes, never worn" idea) and deep-freezes too.

- "Print" ends - "Months later, the sun picked out/ her paw on the pane, each tip,// tiny as peas. I peered close,/ nose almost almost touching my fossil,// backlit on the glass" - We have prints too, and photocopied hands. Companies offer casts. Why paw? Human prints don't look like that, do they? This isn't the other poem that compares babies to animals.

At the end of "My Neighbour's Himalyan Birch" the "I" notices "its skeleton of bark// and think of other deciduous things:/ antlers, wings, her teeth that never came." Why skeleton? A skeleton of branches I could understand. Why the gaping stanza break? And would the bark really bring those items to mind? "Mothers of the Dead" is all plot, so why the disruptive line-breaks? What language game is being played here other than the "Please read this as Poetry" game? "Repair" is very telly. Why all those empty lines? "Hyperemesis Gravidarum" has a little flourish at the end, but it's prose.

In "As Owls Do", there's "cave ... flight ... twist of your head ... featherweight of baby ... wingbeats of your heart" - imagery that I find rather confused. "Clothes" begins "Left in a loft, a baby's clothes will yellow./ That's what I was told and I thought of my// dead baby's things, stuffed into sacks,/ stirring with a benign mould, A year later// and pregnant, I yanked plastic bags/ from their muggy, attic dark." The breaks only emphasise the blandness - just another loft poem. At the end of "Welcome", "Mersey gulls/ swooped in semi-dark, cawing their applause." Does cawing ever sound like applause? What should we think of a persona who believes so? "Lost" introduces its idea by line 3 then labours the point to little effect. And yet, it was shortlisted in the Bridport and MsLexia competitions, and a prizewinner in the Troubadour, so I'm probably missing something.

Water imagery dominates several of the poems -

- I like "A Dream of Heart Babies". Their mothers are "Gathered on deck", there's "a shoal of heart babies ... Their pulses echo/ for nautical miles,// in a search for chambers/ more complex than coral". In the nets "The catch rises, drips/ and bulges, spills glistening// infants, like oysters at our feet./ Each one cups a new heart". The fish become infants become (opened?) oysters, but otherwise I think it's a powerful piece.

- "Severe Ebstein's Anomaly" starts out as if it's another surreal sea-trip. The parents "set out// for the island of disease beating/ in her body. Her breath in our sails". Reaching the island they find the faulty dam, the redirected river. The scene changes. Suddenly the parents are helplessly watching doctors try to save their child. "a man, head bent, his mouth aflood with tender vowels/ tugs us to her bedside to grant him/ the undocking and let her come adrift". I nearly like this too. The "fantastic voyage" aspect isn't too invasive. I wondered how "aflood" was supposed to tie in with the dam and the river, and there are complications about who/what is the island, whose boat it is, etc.

- In "The Postmistress" a boy isn't after all lost to the waters in a missing boat.

- "Stretch Marks" begins "My swims kept those scars at bay". Here as elsewhere I wonder whether the poet's in control of secondary effects, whether the poet's blinded by the headlamps - is the use of "bay" intentional in the context of swimming?

- "My animal" begins with "Amphibian" emerging from the womb, then worm, chick, piglet, mole and cat. Too easily done.

"Last Poem" (only c.130 words, though it tries to fill a page - Parkinson's Law?) at the end of the book might be a good place to start if you're browsing in a bookshop. I suspect that if you like it, you'll like a lot of the other poems. I'd have preferred a pamphlet of diary entries with a handful of poems - which would be unmarketable. And there's the rub.

No comments:

Post a Comment